Marubi National Museum of Photography

- Written by Portal Editor

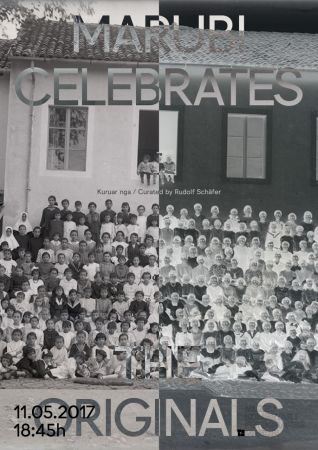

Marubi Celebrates the Originals, curated by Rudolf Schäfer May 11 - July 30, 2017 at the Marubi National Museum of Photography

In the context of photography, talking about originals is a question of dispute. That is why Walter Benjamin, one of the first media philosophers of classical modernism, in his book “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” has denied photography its original character when compared, for example, with the unicum of the painting. His statement is – the photo has no aura!

The term “original print” a.k.a. “vintage print” refers to a positive in photography which was produced by the photographer, or under his supervision, immediately after the negative was created. They are the “originals” of the medium photography. A number of different copies can be produced from one negative by different persons. Vintage prints were usually signed or numbered by the photographer. In the art market, however, vintage prints are also known as prints that have been produced using printing methods that are no longer customary today. Handprints are rare and often of the highest craftsmanship, since possible technical errors are adjusted by the photographers using careful post-processing and the prints are also intensively processed for artistic reasons.

Vintage prints by famous photographers are almost always handprints. The gelatin silver process was the most frequently used image carrier of a black-and-white print in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Other methods were used less frequently due to their technical outlay and the high costs. On average, there were made no more than eight to ten prints per negative. Of these, only a few have survived. Most of the photographs shown here are the last still existing prints of a negative preserved in the Marubi Museum.

Digitization has transformed photography from a “reality and truth medium” into an “image medium among others”, says Urs Stahel, founder of the Fotomuseum Winterthur in Switzerland. Despite this, it remains connected to the “scanning of the world” and the images are mainly used for communication in the social networks. The picture of the smartphone is available worldwide in the social networks. Saved and barely printed, they are sent via SMS, Facebook and other digital media. Whether it is possible or not to secure contemporary photos in the long term, as the Marubi Marubi has done, remains an unsolved case.

One question concerning the preparations for the exhibition has always intrigued me. The Marubi studio left behind a hundred thousand negatives. Today they are professionally stored and researched safely by the Marubi Museum. All very vulnerable and many of them of fragile glass. Why was it so hard to find the originals, the vintage prints? The Marubi Museum left few of them and the museum did not have enough time to buy new collection objects. In my opinion, there is on the one hand the work of a photo atelier, who is responsible for the great rarity of the vintage, the pictures are sold and the negatives are archived if the customer reorders. On the other hand, there is the question, who was the normal customer of the “Dritëshkronja Marubi” studio from 1858 to 1945 and how this changed during the communist regime?

With Enver Hoxha’s rise to power in 1944, groups of people were persecuted and referred to as enemies of the people and counterrevolutionaries deported in camps or even executed. The photos were hidden as dangerous evidence and often destroyed. It would be very worthwhile if our exhibition helps to counter the amnesia of the past, especially the Hoxha-Dictatorship.

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun.

–––

Exhibition opening

Thursday May 11, at 6:45 PM

Curator’s talk

Friday May 12, 2017 at 6 PM

Please read as well: