A cloudy, rainy day had brought us back to Weimar in the past few days, “best” weather to visit the still relatively new Bauhaus Museum, which was opened to the public on April 5, 2019.

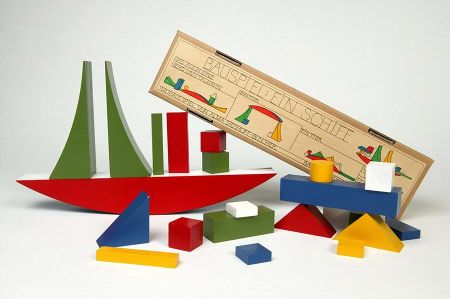

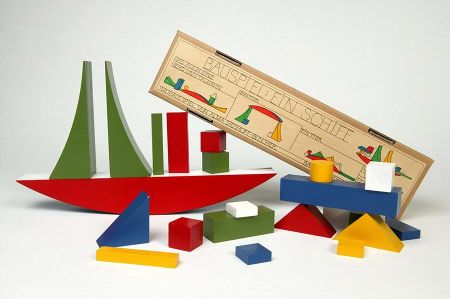

We had already visited the small shop in Weimar city centre several times and particularly admired the “colourful ship” designed by Bauhaus student Alma Siedhoff-Buscher and initially handcrafted, which was “a ship – also a mountain and valley railway, a gate, an animal and many other things.”

The colourful ship by Alma Siedhoff-Buscher

This ship, probably the best-known design by one of the so-called Bauhaus students, was groundbreaking in the field of toy design, especially since it was also made into a film, and thus contributed not insignificantly to the change in craft and industrial history, like many other Bauhaus designs. Although the toy no longer meets today's standards of safety regulations for children's toys, it clearly shows what change could have occurred through new thinking and creation, starting with the children from the first German democracy and its approaches. Unfortunately, and as is well known, the resulting dictatorship of the Third Reich also stopped this progress. Hopefully something like this never happens again.

This ship, probably the best-known design by one of the so-called Bauhaus students, was groundbreaking in the field of toy design, especially since it was also made into a film, and thus contributed not insignificantly to the change in craft and industrial history, like many other Bauhaus designs. Although the toy no longer meets today's standards of safety regulations for children's toys, it clearly shows what change could have occurred through new thinking and creation, starting with the children from the first German democracy and its approaches. Unfortunately, and as is well known, the resulting dictatorship of the Third Reich also stopped this progress. Hopefully something like this never happens again.

We have already reported on the model house “Am Horn” by Georg Muche from 1923, which was built as part of the first Bauhaus exhibition in Weimar. For the first time, new ideas and connections, such as internal activity paths and functions in modern housing construction, were implemented here. More than 100 years have now passed, which is one more reason to visit the Bauhaus Museum, as a large number of artifacts from that time are on display here.

We have already reported on the model house “Am Horn” by Georg Muche from 1923, which was built as part of the first Bauhaus exhibition in Weimar. For the first time, new ideas and connections, such as internal activity paths and functions in modern housing construction, were implemented here. More than 100 years have now passed, which is one more reason to visit the Bauhaus Museum, as a large number of artifacts from that time are on display here.

The starting point and unique selling point in the Bauhaus Museum are the historical collections of the Klassik Stiftung Weimar on the prehistory, history and aftermath of the State Bauhaus, which was founded in Weimar in 1919. The collection has grown significantly since 1990 through purchases and donations. With the Gropius Collection, the Klassik Stiftung also owns the oldest Bauhaus holdings in existence. In the entrance area there is a detailed reference to the model house “Am Horn”, which is the only surviving experimental house from the Bauhaus period in Weimar and can also be viewed as an independent museum (UNESCO World Heritage Site).

Gropius “Art and Technology – a New Unity”

It continues with textual and visual representations from the time after the lost First World War, the first democracy on German soil, which largely had its origins in Weimar. From this, the educational, artistic, architectural and design ideas of the Bauhaus and their teachers emerged, which continue to radiate around the world to this day, which is already conveyed by the first glance at the visitors present: it is rare to meet such a large number of international guests at one location. Many groundbreaking concepts were initially conceived for Weimar. The presentation in the Bauhaus Museum Weimar shows works by Walter Gropius, the founding director of the Bauhaus, as well as by the Bauhaus masters such as Lyonel Feininger, Gerhard Marcks, Johannes Itten and Paul Klee. In addition, numerous student works, including works by Marcel Breuer and Alma Siedhoff-Buscher, will be presented, which demonstrate the practice-oriented training at the Bauhaus. Training concepts that had not been practiced for years and were only rediscovered in some cases in the mid-1980s. Just to introduce the term holistic, practice-oriented learning.

Numerous objects on display illustrate the complexity, creativity and liveliness of school work in Weimar. Based on the Bauhaus manifesto and program, the Bauhaus masters developed novel teaching programs with the preliminary courses by Itten, the theory of shapes and colours by Klee and Kandinsky and training in various workshops. The workshop principle, the practice-oriented craftsmanship and artistic training of an average of 150 students, was just as characteristic of the Bauhaus as the teamwork of teachers and students. The transition from a one-off handcrafted piece to a prototype for industry from 1922 onwards, in keeping with Gropius' motto "Art and technology - a new unity", was documented in the Bauhaus Museum Weimar by the design classics that have been produced to this day, such as the Bauhaus chess by Josef Hartwig Table lamp by Carl Jakob Jucker and Wilhelm Wagenfeld or metal work by Marianne Brandt.

Striking Bauhaus lamp – form follows function

The design of the Bauhaus lamp, which was sensational at the time, was made of nickel-plated metal and glass and was produced in various models at the time. Only the lampshade in the shape of a 5/8 ball was made of opal glass, which diffuses the light from the lamp. Until then, opal glass had only been used in lighting fixtures in the industrial sector, so the Bauhaus lamp was the first electric lamp that enabled diffused light in living spaces. The lamp holder is supported by a cylindrical shaft made of either metal or clear glass, although in glass models there is a metal tube that houses the power cable. In the preliminary design, Carl Jacob Jucker led the power cable directly through the glass shaft; Wagenfeld added the nickel-plated metal pipe in 1924. The outer power cable is covered with textile. There is a characteristic grommet on the shaft from which the cord of the pull switch leads; the end of the cord has a nickel-plated metal ball. The round base of the lamp is also made of either metal or shimmering green clear glass.

With the use of simple geometric shapes such as the round base and the cylindrical shaft, Wagenfeld and Jucker achieved both “maximum simplicity and the highest economic efficiency within the time and available materials” in keeping with the design principle “form follows function.”

The lamp was designed in the Bauhaus metal workshop from 1923 onwards after László Moholy-Nagy reorganized it as the new “form master”. Walter Gropius pushed through the reorientation of the Bauhaus against the artistic intentions of Johannes Itten and set the goal of producing mass-producible products that were to be developed collaboratively using new materials. Jucker used components from Gyula Pap and showed the still unfinished lamp with a glass river and column at the 1923 Bauhaus exhibition in the model house “Am Horn” in the fall. Wagenfeld placed a metal lamp next to it in 1924.

An attempt was made to market the lamp commercially as early as 1924, but this failed because most of its components had to be handmade in the Bauhaus workshop. But even when the lamp was first offered for industrial production by Schwintzer & Gräff in 1928, the Bauhaus lamp was unaffordable for large sections of the population at 55 Reichsmarks.

In the associated work laboratory, visitors can experimentally discover how design processes still shape everyday life today. The starting point are questions from the historical Bauhaus about living together, self-presentation and shaping the future.

A fascinating first tour that will definitely be followed by others.

Please read as well:

Ceramic workshop at the Bauhaus in Dornburg

With a view of the Saale, we hike to Dornburg