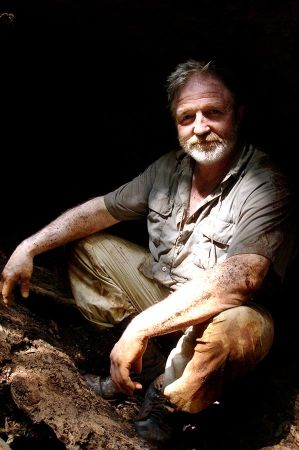

George McGavin – former Oxford University entomologist

- Written by Portal Editor

Today's entomological collection at the Natural History Museum at the University of Oxford is huge, as it contains over five million insects.

After a visit with George McGavin, we jokingly joked that it would probably take the life's work of at least three carpenters to make all the drawer cabinets for storing the insects. But one after another.

First chance meeting in the pub near Oxford University

As part of the English course, we went to London with a group of trainees for a multi-day on-site practical language course, with a day trip to Oxford also included in the program. It was pure coincidence that we met Prof. Dr. in a nearby pub in the evening. Met George McGavin, who was drinking his after-work beer there. We quickly found ourselves so deeply involved in conversation that we almost missed the trip back to London. However, we agreed that we should meet again whenever possible. The contact addresses were quickly exchanged, and the first telephone contact followed the following day; there was too much interest in the university's insect collections described by George. Just two days later there was another meeting at the University of Oxford, which, following further excursions to London, was to become a regular part of the program of regular visits with trainees.

As part of the English course, we went to London with a group of trainees for a multi-day on-site practical language course, with a day trip to Oxford also included in the program. It was pure coincidence that we met Prof. Dr. in a nearby pub in the evening. Met George McGavin, who was drinking his after-work beer there. We quickly found ourselves so deeply involved in conversation that we almost missed the trip back to London. However, we agreed that we should meet again whenever possible. The contact addresses were quickly exchanged, and the first telephone contact followed the following day; there was too much interest in the university's insect collections described by George. Just two days later there was another meeting at the University of Oxford, which, following further excursions to London, was to become a regular part of the program of regular visits with trainees.

Oxford has a number of museums and galleries that are open to the public free of charge. Founded in 1683, the Ashmolean Museum is the oldest museum in Britain and the oldest university museum in the world. It houses significant collections of art and archaeology, including works by Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, William Turner and Pablo Picasso, as well as ancient treasures such as the Scorpion Mace, the Parian Chronicles and the Alfred Jewel. It also contains a Stradivarius violin, considered one of the best-preserved examples in the world.

Oxford has a number of museums and galleries that are open to the public free of charge. Founded in 1683, the Ashmolean Museum is the oldest museum in Britain and the oldest university museum in the world. It houses significant collections of art and archaeology, including works by Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, William Turner and Pablo Picasso, as well as ancient treasures such as the Scorpion Mace, the Parian Chronicles and the Alfred Jewel. It also contains a Stradivarius violin, considered one of the best-preserved examples in the world.

The University Natural History Museum houses the university's zoological, entomological and geological exhibits. It is located in a large neo-Gothic building on Parks Road in the university's science park. Its collection includes the skeletons of a Tyrannosaurus and a Triceratops as well as the most complete remains of a dodo in the world. It also houses the “Simonyi Professorship for the Public Understanding of Science”.

History with incredible consequences – louse on the wine

How did this incredible collection of insects come about? Here is a partial anecdote that is partly responsible for the expansion and size. Oxford is the oldest university in the English-speaking world and is known to have existed since the 12th century, so it's clear that collecting insects began much earlier. We were later lucky enough to see some specimens from the 14th and 15th centuries, which are long extinct.

How did this incredible collection of insects come about? Here is a partial anecdote that is partly responsible for the expansion and size. Oxford is the oldest university in the English-speaking world and is known to have existed since the 12th century, so it's clear that collecting insects began much earlier. We were later lucky enough to see some specimens from the 14th and 15th centuries, which are long extinct.

In 1863, J.O. Westwood, professor of entomology at the University of Oxford, a package of plant samples containing a few vine leaves with gall-like growths. In one of them, the researcher discovered an insect that was small and unknown to him. Westwood noted a few observations and then forgot about it.

At around the same time, a few vines died in a winery in Pujaut near Tavel (Côtes du Rhône). They do not suffer from any of the previously known vine diseases. But nobody pays attention to this fact either. Four years later, the manager of a winery near Arles addressed a letter to the president of the regional agricultural committee. Vines have been dying on his winery for two years without him being able to find the cause.

It takes months for the regional authorities to react. They entrust Henri Marès to investigate the problem. Marès, celebrated inventor of the method of combating powdery mildew with a sulphur solution, goes to an affected vineyard near Carpentras, notes the symptoms without getting to the bottom of their cause and downplays the importance of the phenomenon.

It takes months for the regional authorities to react. They entrust Henri Marès to investigate the problem. Marès, celebrated inventor of the method of combating powdery mildew with a sulphur solution, goes to an affected vineyard near Carpentras, notes the symptoms without getting to the bottom of their cause and downplays the importance of the phenomenon.

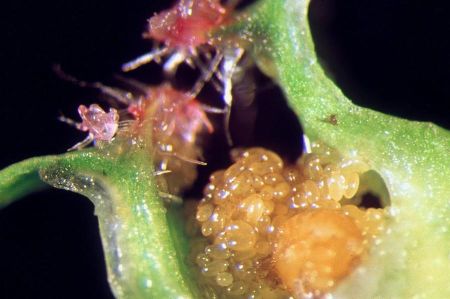

In July 1868 a second commission was formed. It consists of Jules-Emile Planchon, professor at the Pharmacy School of Montpellier, the agronomist Gaston Bazille and the gardener Félix Sahut. The three experts tear an infected vine out of the ground at a winemaker named de Langloy in Saint-Martin du Crau (near Saint-Remyde Provence). They believe there is a fungal infection and are looking for witnesses with magnifying glasses out. They do not find a fungus, but a small louse of yellowish colour, sticking to the wood and sucking its sap.

A louse? No, there are thousands of lice in different stages of development. They are everywhere, at the deepest roots as well as at the most superficial. After some back and forth, the pest is named Phylloxera vastatrix.

Meanwhile, the Englishman J.O. Westwood, professor of entomology, resumed his research, discovered the insect and gave it the name Peritymbavitisana. The name Phylloxera is not appropriate because the insect lives in both the roots and the leaves, but Phylloxera only refers to the latter: “I follow the development of a nymph and witness the hatching of an elegant insect with four transparent little wings. This makes it clear: the insect originally named Rhizapis ('that which lives in the roots') is a phylloxera,” Planchon replied in 1874. And forgets to mention that the first person to identify Phylloxera in Europe was the Parisian entomologist Signoret, to whom the physician and pharmacologist Planchon, who knew little about insects, sent a few specimens for analysis. And that it was not he, Planchon, who discovered the winged form of the insect, but the veterinarian Pierre Boiteau from Villegouge near Bordeaux, who was awarded a gold medal for this by the French Ministry of Agriculture.

Meanwhile, the Englishman J.O. Westwood, professor of entomology, resumed his research, discovered the insect and gave it the name Peritymbavitisana. The name Phylloxera is not appropriate because the insect lives in both the roots and the leaves, but Phylloxera only refers to the latter: “I follow the development of a nymph and witness the hatching of an elegant insect with four transparent little wings. This makes it clear: the insect originally named Rhizapis ('that which lives in the roots') is a phylloxera,” Planchon replied in 1874. And forgets to mention that the first person to identify Phylloxera in Europe was the Parisian entomologist Signoret, to whom the physician and pharmacologist Planchon, who knew little about insects, sent a few specimens for analysis. And that it was not he, Planchon, who discovered the winged form of the insect, but the veterinarian Pierre Boiteau from Villegouge near Bordeaux, who was awarded a gold medal for this by the French Ministry of Agriculture.

While vain scientists fight over appropriate names and argue about where the louse spends its days and who should go down in history as the discoverer of phylloxera, the phylloxera continued its work of destruction unhindered. A year after her official discovery, she appears in Bordeaux. In 1879, two thirds of the French vineyard area was infested with the pest. This is a small hint of the blatant importance that insects, no matter how small, can have for us and the environment. But now back to George McGavin.

An entomologist who can also mediate

A really formative and at the same time first puzzling task was at the forefront right at the beginning of the visit with a small group of trainees, when it was about the above-mentioned louse and, in comparison, mayflies, which he presented to us in various facets. Task: Imagine husband and wife Mayfly having sex early in the morning, their countless children right afterward and also their grandchildren, etc. etc., because Mayfly! There are no natural enemies, not even humans, to interrupt this production in one day. And all flies experience at least the next 24 hours. How many mayflies are there after 24 hours? Rarely have I seen such attentive, interested and calculating young people, who also exchange ideas very lively. When the result was declared to be the size of a sphere with the diameter of the Earth and the Moon, the experience was perfect. The interest in further lectures without any intervening remarks, as parallels were repeatedly drawn with regard to humanity. Simply exciting.

A really formative and at the same time first puzzling task was at the forefront right at the beginning of the visit with a small group of trainees, when it was about the above-mentioned louse and, in comparison, mayflies, which he presented to us in various facets. Task: Imagine husband and wife Mayfly having sex early in the morning, their countless children right afterward and also their grandchildren, etc. etc., because Mayfly! There are no natural enemies, not even humans, to interrupt this production in one day. And all flies experience at least the next 24 hours. How many mayflies are there after 24 hours? Rarely have I seen such attentive, interested and calculating young people, who also exchange ideas very lively. When the result was declared to be the size of a sphere with the diameter of the Earth and the Moon, the experience was perfect. The interest in further lectures without any intervening remarks, as parallels were repeatedly drawn with regard to humanity. Simply exciting.

George McGavin was Assistant Curator of the Oxford Museum's entomological collections of over five million insects from 1984 to 2008. They come from different families and from all over the world and some were collected more than 150 years ago, not just since the louse on the wine.

McGavin attended Daniel Stewart's College, a private school in Edinburgh, and then studied zoology at the University of Edinburgh from 1971 to 1975, followed by a doctorate in entomology at Imperial College, London. He then taught and researched at the University of Oxford. He is an Honorary Research Associate at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History and the Department of Zoology, Oxford University, where his interests are listed as “Terrestrial arthropods, particularly in tropical forests, caves and savannahs.” He is also visiting professor of entomology at the University of Derby.

George is a Fellow of the Linnean Society and the Royal Geographical Society and has several species of insects named in his honour. He was previously Associate Curator of Entomology at the University of Oxford's Museum of Natural History.

George is a Fellow of the Linnean Society and the Royal Geographical Society and has several species of insects named in his honour. He was previously Associate Curator of Entomology at the University of Oxford's Museum of Natural History.

George also lectured at the Cheltenham Science Festival, delivered the Royal Geographical Society's Children's Christmas Lecture and contributed to their school program. He won the Earthwatch debate 'Irreplaceable - The World's Most Invaluable Species', broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 2008 and he is a lecturer on board Cunard ships. In 2017 he gave the Royal Entomological Society's Verrall Lecture on "Stories from TV: an entomologist's perspective".

He is a patron of the Bees, Wasp and Ants Recording Scheme and Alderney Records Center charity Wildscreen and he is President of the Dorset Wildlife Trust and a global ambassador for Earthwatch.

He was also a lecturer at Trinity College and then at Jesus College. After a 30-year academic career, he became a television presenter, working mainly for productions at the BBC Natural History Unit in Bristol. His programming credits include the BBC series Lost Land, Prehistoric Autopsy, Miniature Britain, Planet Ant, Ultimate Swarms, Dissected: The Incredible Human Hand and Foot, Monkey Planet and the multi-award-winning documentary “After Life: The Strange Science of Decay.” His most recent show, The Oak: Nature's Greatest Survivor, won a Royal Television Society Award and a Grierson Award.

He was also a lecturer at Trinity College and then at Jesus College. After a 30-year academic career, he became a television presenter, working mainly for productions at the BBC Natural History Unit in Bristol. His programming credits include the BBC series Lost Land, Prehistoric Autopsy, Miniature Britain, Planet Ant, Ultimate Swarms, Dissected: The Incredible Human Hand and Foot, Monkey Planet and the multi-award-winning documentary “After Life: The Strange Science of Decay.” His most recent show, The Oak: Nature's Greatest Survivor, won a Royal Television Society Award and a Grierson Award.

A comprehensive handbook he wrote covers all 29 orders of insects, as well as spiders and terrestrial arthropods. It is packed with hundreds of annotated photos and illustrations to help readers and users recognize the many species of insects, and provides a brief description of each insect family with key characteristics, including life cycles, the environment in which they thrive, and a photographic guide, which helps categorize the group of insects. It is an essential guide for beginners and enthusiasts alike.

Smithsonian Handbooks are the most visually appealing field guides on the book market. With more than 500 full-colour illustrations and photographs, as well as detailed notes, the Smithsonian Handbooks make identification easy and accurate.

Please read as well: