Migration to Hermannstadt - today Sibiu in Transylvania

- Written by Portal Editor

When there are wars and conflicts at home, when there is no work even in agriculture for self-sufficiency due to destruction or epidemics, people are desperate, seeking about ways out and away from misery, not to be killed or even starve because of hunger.

This aspiration has existed since the beginning of human history, it is probably also the self-preservation instinct to attribute (which is more than natural) and repeats itself continuously and permanently (today Syria, Afghanistan, Africa, but also the Balkans). We are “happy” to close our eyes to these realities, a few real helpers are often looking desperately for solutions, but then again to experience the same misery elsewhere with other stakeholders.

It is often forgotten that there has been misery in Western Europe, indeed in Germany, not only in the Middle Ages but also in the recent past. Perhaps it helps a bit further to know the story and the consequences of understanding why people cannot be “forced” to leave their native homeland of their own volition. Such an example in history is Hermannstadt, today Sibiu in Romania, where probably the first German settlers reached this region in 1147; They settled on the hill above the Zibin River, today's Upper Town.

Settlement of Transylvania by German settlers

If one deals with the descent of these people, their areas of origin mostly lie in the areas of the bishoprics of Cologne, Trier and Liège (now between Flanders, Wallonia, Luxembourg, Lorraine, the Westerwald and the Hunsrück into Westfälische). Part of the settlers (in North Transylvania) came from Bavaria. The majority, however, came from Middle Rhine and Moselle Franconian. This group of settlers was in no case homogeneous, but contained, besides the German-speaking groups, also Old French-speaking Walloons and Dutch.

The folk legend describes the settlement of the predominantly German settlers as a process in which the settlers, who had had it very bad life in their homeland (which is in fact covered by reports of famines and epidemics from the first half of the 12th century in the bishoprics of Trier and Liège), would have found their own way to Transylvania. At the first resting place in Transylvania, the settlers had consulted and some settlers had settled for staying on the hills (where today lays Sibiu).

The folk legend describes the settlement of the predominantly German settlers as a process in which the settlers, who had had it very bad life in their homeland (which is in fact covered by reports of famines and epidemics from the first half of the 12th century in the bishoprics of Trier and Liège), would have found their own way to Transylvania. At the first resting place in Transylvania, the settlers had consulted and some settlers had settled for staying on the hills (where today lays Sibiu).

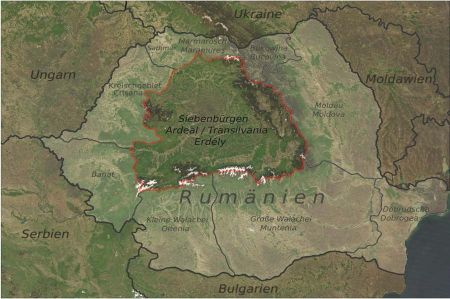

The region of (historic) Transylvania in today's Romania

Source Own work, based on NASA Visible Earth The Carpathian Mountains. Credit: Jeff Schmaltz, MODIS Rapid Response Team, NASA/GSFC, Author DietG

As a sign of taking possession of the country, the two leaders Hermann and Wolf are said to have pushed two large swords crossed into the ground. These crossed swords since the time formed the coat of arms of the settlement Hermannsdorf (later Sibiu). Other groups of settlers would then split up and move north and east.

Saxons are recruited - like guest workers in the 60s

The arrival of the Transylvanian Saxons happened in the context of the German East settlement. The settlers were professionally recruited by locators and immigrated in several spurts in appropriate mass to Transylvania. Their route took them via Silesia, Saxony or Bohemia (assuming there was an intermediate home) via the Zips to Transylvania, or via the Danube and the Mieresch. The first settlements took place around 1150 under King Géza II.

This settlement was based on set priorities, so targeted villages and towns were established and enforced the internal settlement. The first 13 primary settlements in the Sibiu chapter were Sibiu, Stolzenburg, Großscheuern, Burgberg, Hammersdorf, Neppendorf and Schellenberg; in the Leschkirch chapter it was Alzen, Kirchberg and Leschkirch as well as Großschenk, Marlingen and Schoenberg in the Schenker chapter. Even the number of first settlers can be calculated by researching the corridor and hoof classification of Saxon communities. The settlements initially consisted of always the same number of a little more than 40 hooves, means about 40 farmsteads. 13 settlements of 40 hooves give 520 hooves (farmsteads). Assuming an average family size of five persons, conservative estimates give a figure of 2600 persons. Further inflows over the following years and decades (also from the areas of origin) are likely. From the primary settlers in the time settlers poured in start-ups and little developed area. Starting from the chairs Sibiu, Leschkirch and Großschenk, the royal soil, the Burzenland and the Nösnergau were settled. In addition, internal settlement also took place on aristocratic soil.

Only in the course of the centuries this colorful community of settlers did form a true people with their own cultural memory, their own language, their own law (own land law) and autonomy administration (nation university).

Stephan II relies on German noblemen, artisans, miners and farmers

In addition, they were not the only Germans in the former Hungary, since Stephan II had repeatedly called German nobles, civil servants, artisans, miners and peasants to various parts of his empire. In this development, the settlement of the Transylvanian Saxons is classified. Geisa II, King of Hungary, had expanded its sphere of influence across Transylvania to the Carpathian crests in the middle of the twelfth century and had the area, which at first was very sparsely populated, developed by the German settlers.

In order for the settlements to develop quickly and to generate corresponding tax profits for the state, he gave the settlers special privileges, as he had previously done to the aid people of the Szeklers. In it, they were initially granted various privileges (Freitümer) and granted certain tax and economic benefits. These rights were codified in 1224 in the Goldene Freibrief (Andreanum) under Andreas II. In addition to the free use of water and forests and duty free for the German traders, the settlers were also neither the nobility nor the church submissive and thus free citizens (in the sense of the then Understanding of active citizens, ie male, tax-paying and adult).

The young settlements developed rapidly. The population increased rapidly due to influxes and birth surpluses, but was considerably decimated by the Mongolian storm of 1241. The country was heavily set back in its development. In some settlements, only two to three generations had lived before they became deserted by the attacks of the Mongolian riders. However, the recovery was relatively fast, the internal settlement gained momentum again. After the country's construction in the 12th and 13th centuries, a long period of prosperity followed.

Economic heyday of the Transylvanian Saxons

The first period of great cultural and economic prosperity of the Transylvanian Saxons is therefore to settle in the 14th and 15th centuries. The population of the Seven Chairs and the other districts of Königboden grew rapidly and steadily. In the mines of the Carpathians and in the Rodna Mountains, gold, silver and salt were mined. Trade flourished and the economy was able to develop. The routes of the Saxon merchants ranged from Danzig on the Baltic Sea via Krakow, Vienna, and Belgrade to Constantinople and the Crimea. Until 1395 (first Turkish invasion), there were no major external threats, and the upswing of German settlements now led to the formation of real urban centers. Sibiu, Kronstadt, Cluj-Napoca, Bistrita, Schäßburg and Mühlbach became towns, other places such as Agnetheln, Broos, Biertan, Marktschelken, Mediasch and Saxon rain market towns. The craft was already diversified. Thus, in the oldest surviving guild regulations of the seven chairs of 1376 already 19 guilds and 25 trades are noted. From the middle of the 15th century, the cities of the royal estate (especially Kronstadt) became so financially strong that they lent money to the Hungarian king against the pledging of entire places.

Please read as well:

Kizilca Village - a migration problem in the village

Orhan Pamuk - The EU has forgotten all its values

Piri Reis - first Ottoman world map from 500 years ago

Kyffhäuser Mountainrange and Mythlogy of Barbarossa