The Offenburg milestone from Roman times

- Written by Portal Editor

As already described in the article "Roman milestones, also called miliarium", column-shaped milestones on the Roman roads recorded the distances to the nearest main town.

In the Gallic and Germanic provinces, both the Roman mile (roughly 1.48 kilometres when converted) and the local league (roughly 2.2 kilometres when converted) were used to measure length. The milestones or milestones were also media or "advertising pillars" for state-political propaganda and declarations of loyalty. The milestones almost always contained not only the distance information, but also in their inscription a reference to the emperor as the supreme builder and customer of the road construction. On the other hand, the milestones were often formulated by the building authority, a municipality or the city, as a tribute to the regent. Therefore, his imperial titulature or offices, personal, honorary and victory names are often listed in full.

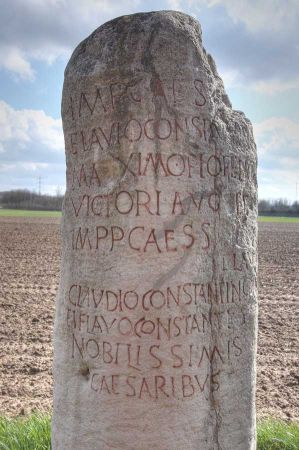

Offenburg milestone – first mention of Strasbourg

The Offenburg milestone is the oldest dateable source for the Roman name of Strasbourg. It originally stood on the so-called Kinzigtalstraße, which led from Argentorate (today's Strasbourg) to the upper Danube. Emperor Vespasian commissioned his special envoy and supreme commander of the army on the right bank of the Rhine, Gnaeus Pinarius Cornelius Clemens, with the construction. His name appears in the fragmented inscription after that of the regent and his two sons, the princes and later emperors Titus and Domitian.

The Offenburg milestone is the oldest dateable source for the Roman name of Strasbourg. It originally stood on the so-called Kinzigtalstraße, which led from Argentorate (today's Strasbourg) to the upper Danube. Emperor Vespasian commissioned his special envoy and supreme commander of the army on the right bank of the Rhine, Gnaeus Pinarius Cornelius Clemens, with the construction. His name appears in the fragmented inscription after that of the regent and his two sons, the princes and later emperors Titus and Domitian.

Kinzigtalstraße shortens the Limes

The construction of the Kinzigtalstraße shortened the connection between the Rhine and the Danube by 160 kilometres. In the past, communication and the movement of troops between the Roman areas there could be made considerably easier. The milestone is considered important and early evidence of the military, administrative and infrastructural development of Upper Germany.

Parallel structures in many other countries

There were comparable uses of the milestones in many other countries along the Roman road system, including Turkey. We were able to admire the so-called Stadiasmus Patarensis very comprehensively, which was reassembled as part of the wall after the excavations and exposures and not only gave information about the distance to the next place, but could also draw attention to previously unknown cities. Here we can only thank Prof. Dr. (em.) Sencer Şahin, who very extensively and freely gave us insights.

There were comparable uses of the milestones in many other countries along the Roman road system, including Turkey. We were able to admire the so-called Stadiasmus Patarensis very comprehensively, which was reassembled as part of the wall after the excavations and exposures and not only gave information about the distance to the next place, but could also draw attention to previously unknown cities. Here we can only thank Prof. Dr. (em.) Sencer Şahin, who very extensively and freely gave us insights.

It remains exciting!

Please read as well: